Tapping Into One’s Inner Resources

On the NPR website there’s an article that really caught my attention, and I think my becoming a personal coach is the reason why. In “How Do Wishes Granted To Very Sick Kids Affect Their Health?” the author, Tara Haelle, describes a study in the journal Pediatric Research about very sick kids who were treated at a pediatric hospital in Columbus, OH. Some of the kids had received “gifts”- things like visits from celebrities, trips, video games, etc. while the other kids didn’t. This was not a formal comparison study, so these two groups of kids aren’t necessarily evenly matched. Nonetheless, the kids who got gifts had significantly fewer emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations than the ones who didn’t receive gifts. The authors speculate something about the mind-spirit-body connection might be behind this.

This article brought me back to a memorable experience I had while I was a hematology fellow in Atlanta. We had a 17 year-old young man on our service named Anthony (not his real name). Anthony was playing basketball with his friends one day when he began to get short of breath. He was brought to the emergency room where he was found to have a hemoglobin (measure of red blood cells) of 4 (normal is 14-16). His body had stopped producing blood cells, a condition called aplastic anemia. In addition to his low red blood cell count, he had almost no white blood cells, placing him at high risk for infections, and almost no platelets (blood cells that help blood clot), placing him at high risk for bleeding.

Anthony was not a candidate for the most effective treatment, a bone marrow transplant because there was no suitable donor for him. We treated him with the best available medical treatments but his blood counts only worsened. At the time of this story he was in the hospital because of a severe infection. He was also bleeding and transfusions were losing their effectiveness. In addition, we were having a hard time because Anthony’s veins were totally scarred from all the blood tests and intravenous treatments he had gotten. He had a fever of 103 degrees, was bleeding from his nose and mouth, and appeared to be dying. And we had no further treatments that we could use for his condition.

We knew Anthony was a huge fan of all Atlanta sports teams and I thought maybe we could get a member of one of the teams to come and visit this critically ill young man. It was summertime and the baseball team, the Braves, were on a West-coast road trip. The basketball and hockey teams, the Hawks and the Flames, were on summer vacation still. But the football team, the Falcons, was getting ready for training camp and players were arriving to town. I spoke to someone from the marketing department and they said “Yes, we’ll send one of our players to meet Anthony tomorrow.”

We pulled out the stops preparing for the player’s arrival. One of the nurses baked a big cake in the shape of a football. We got balloons, streamers, and signs to make Anthony’s hospital room festive. At first we didn’t tell him what was going on but eventually we did and, boy, did his sunken eyes light up. An Atlanta Falcon was coming to visit him!

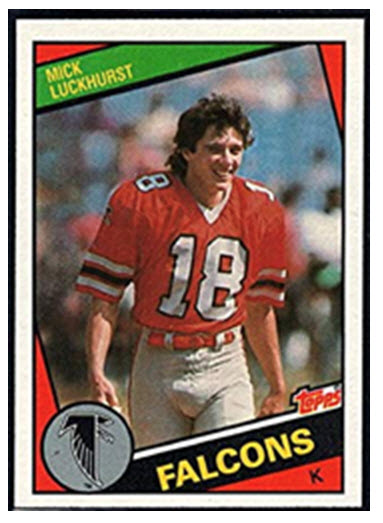

None of us knew who the player was going to be. Maybe it was going to be a burly lineman. Or perhaps an athletic running back, or a fleet wide receiver. We heard the elevator bell ring and a group emerged wearing Falcons gear. In the center was our player- a long-haired, not particularly athletic appearing guy. It was Mick Luckhurst, the field goal kicker. Mick wasn’t even an American- he was a British rugby player who came to the States to play rugby and got enticed to become a placekicker. He was a good one- when he retired in 1987 he was the Falcons’ all-time leading scorer. But was he the kind of football player Anthony was hoping to meet?

We needn’t have worried. Anthony saw Mick enter his room and burst into a huge grin. He recognized him right away. Mick sat down on Anthony’s bed and they spoke about football for the next 30 minutes.

Then we cut the cake, everyone had a slice, and, after wishing Anthony good luck and get well soon, Mick was gone and it was over.

What happened in the ensuing days/weeks/months was what truly makes this story memorable for me. Anthony’s fever gradually resolved as the infection finally cleared. His bleeding diminished, too, as his platelets, while remaining low, stabilized at a level higher than that which requires transfusions. We sent Anthony home and followed him in the clinic. An intervention which was new became available called a Hickman catheter. This was an implanted intravenous catheter through which blood could be drawn and medicines or transfusions infused. Anthony’s scarred veins were no longer a life-threatening challenge.

For the remainder of the fellowship year I followed Anthony in the clinic. His blood counts were still seriously low but not as dangerously low as they’d been. He had an infection or two which gave all of us a scare but he pulled through them without any major issues. My fellowship ended and I went on to the next chapter of my career.

A year after I left Atlanta I called the hematology clinic to speak with the clinic nurse I had worked with. I asked her about my former patients; some were doing well, some had gotten sicker, some had even died. When I asked about Anthony my nurse said, “You’re not gonna believe this. One day he showed up and said that he was feeling better. Sure enough, his blood counts had bounced up considerably. Ever since then they’ve gotten better and better, and now they’re basically normal.”

That’s the story of Anthony and Mick. You can call this an anecdote, which it is. It’s one that supports the article referenced in the beginning of this piece. And it’s one that supports the belief that so many of us carry: that there are things that go beyond medicine and science that are powerful though mysterious. Doing things that help tap into this mysterious space, be it through prayer, meditation, positive thinking, or granting a sick kid’s wish can sometimes be exactly what’s needed, even at times when things seem to be almost hopeless.

And what does this have to do with being a personal coach? The role of the coach is to help people live better, more fulfilling lives as they pursue their vision and negotiate life’s challenges. The way coaches help people achieve these outcomes is be helping them tap into the wealth of resources that reside within themselves: wisdom, creativity, resourcefulness, strength, and so on. I think these resources reside within that mysterious space I referenced above. So you can add being in a coaching relationship to the list of ways to tap into this space. And being there as a coach when this connection to one’s inner resources happens is just as fulfilling to me as what I felt when, as Anthony’s doc, I was part of a team that helped him survive a life-threatening illness and get home and well again.