by Jeffrey Cohn | May 16, 2020 | People with Cancer / Families

When I was a kid, I was a fan of comic books. In those days it was the DC universe, with Superman/Action Comics issues my most coveted possessions. Interestingly, I found myself particularly drawn to the stories that had him dealing with the challenges posed by the various shades of Kryptonite. Even though he always survived these encounters, somehow the fact that, at least briefly, the Man of Steel could be vulnerable to anything drew me in, perhaps allowing me to see that I had something in common with Superman, after all. That vulnerability became part of my later fandom of Batman, since he was not invulnerable at all. Then when Marvel comics entered my consciousness, Spiderman became a passion, largely related to he and his alter-ego, Peter Parker, being human and vulnerable to not just super-villains, but also the tribulations of daily life, like being dismissed by girls, struggling in class, and looking like a nerd.

I’ve been thinking a lot about vulnerability these days, especially as it pertains to my former life as a healthcare provider. During this pandemic people on the frontlines are coming face to face with their own physical vulnerability. We’ve heard about the shortages of personal protective equipment, and even when one is wearing all the appropriate garb, they likely have moments as they are doing their jobs caring for people with COVID-19 where they feel they’re putting their lives at risk, as well as perhaps putting their families at risk. On top of that, the institutions they’re working for are facing major economic challenges and their very livelihood may be at risk, since furloughs and layoffs have started, with more to follow without a government rescue or quick turnaround.

As people are confronting this vulnerability, they seem to be increasingly willing to share what they’re feeling with their families, their peers, their friends, people they used to be close with that they’ve lost touch with- almost anyone that they have or have had a trusting relationship with. In sharing their fears about being so vulnerable, they’re actually making themselves even more vulnerable- intentionally! I think the reason for this is that they’ve discovered that allowing oneself to be vulnerable in front of others that are (or you’d like to be) close to you builds trust, strengthens relationships, and feels good. This state of trust, mutual respect, and empathy is known as psychological safety. When one feels that they can say something that seems risky it’s because they feel psychologically safe. This invites others to join them in this place of safety, where important things can be discussed that, absent psychological safety, go unsaid, to the detriment of the individual, to relationships, and to the team.

I’m thinking that today’s superheroes have embraced their vulnerability. They are willing to stand like this woman- exposed, taking risks, inviting others to join them…and safe. At a time where we’re all more physically vulnerable than we’re used to, we need to create havens of safety wherever we can. We are vulnerable- expressing that vulnerable, being vulnerable creates that safety we all sorely need.

by Jeffrey Cohn | May 6, 2020 | People with Cancer / Families

I recently reread Andrew Zoll’s amazing book “Resilience” and I couldn’t help applying virtually every concept to our current global Covid-19 crisis. Zoll describes systems that are “robust yet fragile (RYF).” Things work well when circumstances and risks are normal, but in the face of unanticipated threats their underlying fragility becomes apparent. Emphasis/overemphasis on efficiency may lead to systems being too “lean” to have the demand capacity needed to respond to the new threat. Added layers of complexity in the system that come through years of patchwork planning and growth also contribute to its fragility and difficulty bouncing back. I think this RYF framework applies to many systems that are tremendously disrupted at present, including airport security screening, childcare, and our healthcare system itself (if you even want to call it a system).

Looking ahead, Zoll identifies a number of personal and group characteristics associated with resilience. Here are some of those characteristics, along with what you can do now to be resilient in the face of this pandemic:

Trust – When we trust someone, we’re more apt to interact with them in a collaborative and supportive manner. We are social creatures and human contact, even/especially in the face of social distancing is critical. You know who the people are in your life that you trust the most. These are the ones to be in regular contact with currently- probably not in person, but video calls, telephone calls, even text/email can help you appreciate you’re not in this alone.

Acceptance of our limits – Part of the challenge we’re facing now is how much of what we’re experiencing is unknown. Even what we see play out in other parts of the globe may or may not be applicable to our own national, regional, and personal experience. Having the ability to accept the limits of our understanding, and to recognize that, while planning and coordination is important, we also need to sense/learn in the moment and then take steps based on what’s happening now.

Mindfulness – I can’t say that I’m an expert in mindfulness, but the evidence is strong that taking some time out of one’s day to focus on one’s breathing, emotions, nature can help let go of some of the stress and turmoil we are experiencing now. As so many of us are currently mostly confined to our homes and living in relative isolation, this seems like a great time to incorporate mindfulness practices into your daily routine.

Translational Leadership – Zoll talks about a special type of leadership that is able to support resilience that he calls Translational Leadership. While it may feel comforting for some to have a leader projecting calm reassurance and a “follow me” message, what’s really called for is leadership that can connect people, knowledge, and perspectives. The perspectives need to be diverse so that the “groupspeak” that can plague a decision-making body is suppressed, enabling the ideas and practices that are “positively deviant” to move to the forefront. Translational leaders distribute and delegate authority and decision-making so that things get done quickly, with decisions being made by the people with the most expertise, not the highest place in the hierarchy. If you’re in a position of authority, now’s a time to be a translational leader: your team/organization is depending on you.

by Jeffrey Cohn | Jan 10, 2020 | People with Cancer / Families

For the past 8 months I’ve been learning to be a coach. In order to support the people they work with, coaches help their clients tap into a wealth of resources that they, the clients, have within themselves. These include their values, their motivations, their past successes, and their life lessons.

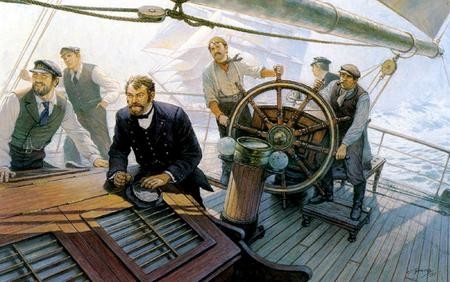

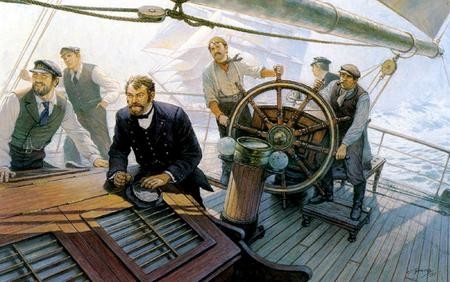

One way of categorizing some of these resources is what the Coaches Training Institute (the program I’m enrolled in) call “The Captain and Crew.” In this model people envision their Inner Leader- their Captain- as well as the different supporting inner perspectives that are the Crew members. By connecting with these resources clients can uncover treasure troves of how they’ve lived their lives that helps them craft the actions they wish to take in order to have even more fulfilling, purposeful lives.

I’m a musical person. I love to listen to almost all kinds of music- it relaxes me, motivates me, and often puts me in a particular mental framework that helps me accomplish whatever I’m trying to do at that time. And, as a child of the 60’s/70’s, I’m a rocker at heart. Recently I created a playlist of songs that I’m finding to be amazingly powerful for me. Each song connects me to a particular member of my own Captain/Crew team, whether it is by the lyrics, the title, the spirit of the music, or anything else. As I listen to the songs I feel the energy from each of these perspectives flow through me. Please allow me to introduce you to my Captain and Crew and the songs that, for me, capture who they are and the resources they have to support me through my life’s journey.

The Captain: “Surf’s Up” by The Beach Boys. My Captain is Mike, a guy in a Tommy Bahama shirt and shorts striding confidently toward me along the seashore. He brings with him a sense of wisdom, confidence, clarity, and certainty regarding how I can live my life according to my own priorities. As I listen to this song I feel myself at the beach and at peace. I find the melody and harmonies to be quite beautiful. To be honest, lots of the words don’t make much sense to me, but “Surf’s Up, aboard a tidal wave, come about hard and join the young and often spring you gave..” gives me a sense of something big happening and I’m a part of it.

The Listener: “Listen to the Music”by the Doobie Brothers. This perspective brings me to the value of being still and fully listening with my whole self. The song is about how listening to the music can connect people to joy and meaning. And I love the tune, the beat- it makes me smile.

Quinn, The Jubilant One: “Walking on Sunshine,” by Katrina and the Waves. I added this Crew member to the model myself. I typically project myself as being pretty serious and this has worked well for me through my life. AND, sometimes, life calls for being joyful, playful, JUBILANT. The person in my life who embodies these qualities more than anyone is my 3 year-old granddaughter, Quinn. When I think of her I sense dance, play, laughter, the joy of living. This song is the most jubilant one I could think of. The words mean little to me except for the title image of “Walking on Sunshine,” which embodies the light, gleeful sensation I’m looking to feel here.

The Intuitive One: “Trust Yourself,” by Bob Dylan. This Crew member helps me access my instincts, what I feel in my soul is the right thing to do/say in the moment. The lyrics are what bring this song to my playlist. “Trust yourself to do the things that only you know best…to do what’s right and not be second-guessed…to know the way that will prove true in the end…to find the path where there is no if and when…”

The Werewolf / The Howler: “Werewolves of London,” by Warren Zevon. I added this Crew member too. Just like every now and then I need to push myself to be more jubilant, I also need to allow myself to howl sometimes. Howling is about being bold, unexpected, cocky, and a bit crazy. As I hear the opening bars of this song I feel my shoulders go back as I stand up straight and begin to stride confidently. I’m “Walking with the Queen, doing the Werewolf of London” and “my hair is perfect.” AWOOOOOOH!

The One Who Forwards the Action and Deepens the Learning: “I’ve Had Enough,” by The Who. This role is about keeping things moving and ensuring lessons are being learned and remembered. I’ve always been a huge fan of The Who. This song from Quadropheniais about the protagonist being at a crossroad, ready to do something different. The opening lyric is especially powerful for me and, I think, has much to do with what many coaching clients bring as a challenge in their lives: “You were under the impression, that when you were walking forwards, you’d end up further onward, but things ain’t quite that simple…” No, they’re not- which is why action and learning is needed.

The Self Manager: “Respect Yourself,” by the Staple Singers. This role is about knowing oneself and maintaining balance and integrity. “If you don’t respect yourself ain’t nobody gonna give a good cahoot.” And this song has real soul, which never hurts….

The Modulator: “Shout,” by the Isley Brothers. I added this Crew member as well. This is to remind myself that, by modulating my tone, my volume, my vocal rhythm, I can invoke very different feelings, and these can lead to different ideas and actions. “A little bit softer now, a little bit softer now, a little bit louder now, a little bit louder now…”

The Curious One: “Learning to Fly,” by Pink Floyd. This Crew member encourages us to be deeply curious as we explore all of what life has to offer. This is one of my favorite Pink Floyd songs. It kind of makes me feel like I’m marching into the unknown. And this lyric really speaks to me: “A soul in tension that’s learning to fly, condition grounded but determined to try, can’t keep my eyes from the circling skies, tongue-tied and twisted just an earth-bound misfit, I…”

The Buffoon/The Anti-Expert: “I Don’t Know,” by The Beastie Boys. I added this Crew member too. For much of my career being an expert was a valuable asset. As I’ve focused on being a change agent, including my current role as a Coach, I realize that being an expert can impede the change being pursued. The more I can “play the buffoon,” believing with true sincerity that I do not have the answers, the more I can help the people with whom I’m working find the actions that work for them. “It’s not so simple as I try to wish, but then again what is? I don’t know, who does know?”

The Appreciator: “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” by The Rolling Stones. This final Crew member is about appreciating all that takes place in life, good/bad/otherwise, for what it is, what it means, and without judgment. I love just about everything about this song: the melody, the harmonies from the choir, the almost spiritual quality to it as one chord builds on another as it nears the end, and the sentiment that, even if we can’t get what we want, we get what we need.

So that’s my Captain/Crew and their playlist. Even just writing this piece about them connects me to their energy and support. I’ve found these resources to be particularly useful for me as I support my clients as a Coach. If I can use my full self with my clients I can be an even more effective Coach. I’m modeling behaviors that may be useful for them. I’m bringing all of my resources to the relationship, and, by doing so, helping my clients tap into the wealth of resources they have within them.

by Jeffrey Cohn | Feb 28, 2019 | People with Cancer / Families

On the NPR website there’s an article that really caught my attention, and I think my becoming a personal coach is the reason why. In “How Do Wishes Granted To Very Sick Kids Affect Their Health?” the author, Tara Haelle, describes a study in the journal Pediatric Research about very sick kids who were treated at a pediatric hospital in Columbus, OH. Some of the kids had received “gifts”- things like visits from celebrities, trips, video games, etc. while the other kids didn’t. This was not a formal comparison study, so these two groups of kids aren’t necessarily evenly matched. Nonetheless, the kids who got gifts had significantly fewer emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations than the ones who didn’t receive gifts. The authors speculate something about the mind-spirit-body connection might be behind this.

This article brought me back to a memorable experience I had while I was a hematology fellow in Atlanta. We had a 17 year-old young man on our service named Anthony (not his real name). Anthony was playing basketball with his friends one day when he began to get short of breath. He was brought to the emergency room where he was found to have a hemoglobin (measure of red blood cells) of 4 (normal is 14-16). His body had stopped producing blood cells, a condition called aplastic anemia. In addition to his low red blood cell count, he had almost no white blood cells, placing him at high risk for infections, and almost no platelets (blood cells that help blood clot), placing him at high risk for bleeding.

Anthony was not a candidate for the most effective treatment, a bone marrow transplant because there was no suitable donor for him. We treated him with the best available medical treatments but his blood counts only worsened. At the time of this story he was in the hospital because of a severe infection. He was also bleeding and transfusions were losing their effectiveness. In addition, we were having a hard time because Anthony’s veins were totally scarred from all the blood tests and intravenous treatments he had gotten. He had a fever of 103 degrees, was bleeding from his nose and mouth, and appeared to be dying. And we had no further treatments that we could use for his condition.

We knew Anthony was a huge fan of all Atlanta sports teams and I thought maybe we could get a member of one of the teams to come and visit this critically ill young man. It was summertime and the baseball team, the Braves, were on a West-coast road trip. The basketball and hockey teams, the Hawks and the Flames, were on summer vacation still. But the football team, the Falcons, was getting ready for training camp and players were arriving to town. I spoke to someone from the marketing department and they said “Yes, we’ll send one of our players to meet Anthony tomorrow.”

We pulled out the stops preparing for the player’s arrival. One of the nurses baked a big cake in the shape of a football. We got balloons, streamers, and signs to make Anthony’s hospital room festive. At first we didn’t tell him what was going on but eventually we did and, boy, did his sunken eyes light up. An Atlanta Falcon was coming to visit him!

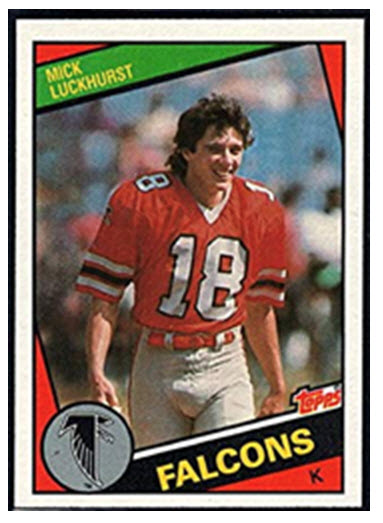

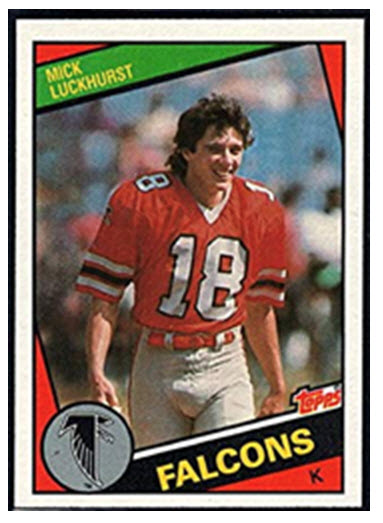

None of us knew who the player was going to be. Maybe it was going to be a burly lineman. Or perhaps an athletic running back, or a fleet wide receiver. We heard the elevator bell ring and a group emerged wearing Falcons gear. In the center was our player- a long-haired, not particularly athletic appearing guy. It was Mick Luckhurst, the field goal kicker. Mick wasn’t even an American- he was a British rugby player who came to the States to play rugby and got enticed to become a placekicker. He was a good one- when he retired in 1987 he was the Falcons’ all-time leading scorer. But was he the kind of football player Anthony was hoping to meet?

We needn’t have worried. Anthony saw Mick enter his room and burst into a huge grin. He recognized him right away. Mick sat down on Anthony’s bed and they spoke about football for the next 30 minutes.

Then we cut the cake, everyone had a slice, and, after wishing Anthony good luck and get well soon, Mick was gone and it was over.

What happened in the ensuing days/weeks/months was what truly makes this story memorable for me. Anthony’s fever gradually resolved as the infection finally cleared. His bleeding diminished, too, as his platelets, while remaining low, stabilized at a level higher than that which requires transfusions. We sent Anthony home and followed him in the clinic. An intervention which was new became available called a Hickman catheter. This was an implanted intravenous catheter through which blood could be drawn and medicines or transfusions infused. Anthony’s scarred veins were no longer a life-threatening challenge.

For the remainder of the fellowship year I followed Anthony in the clinic. His blood counts were still seriously low but not as dangerously low as they’d been. He had an infection or two which gave all of us a scare but he pulled through them without any major issues. My fellowship ended and I went on to the next chapter of my career.

A year after I left Atlanta I called the hematology clinic to speak with the clinic nurse I had worked with. I asked her about my former patients; some were doing well, some had gotten sicker, some had even died. When I asked about Anthony my nurse said, “You’re not gonna believe this. One day he showed up and said that he was feeling better. Sure enough, his blood counts had bounced up considerably. Ever since then they’ve gotten better and better, and now they’re basically normal.”

That’s the story of Anthony and Mick. You can call this an anecdote, which it is. It’s one that supports the article referenced in the beginning of this piece. And it’s one that supports the belief that so many of us carry: that there are things that go beyond medicine and science that are powerful though mysterious. Doing things that help tap into this mysterious space, be it through prayer, meditation, positive thinking, or granting a sick kid’s wish can sometimes be exactly what’s needed, even at times when things seem to be almost hopeless.

And what does this have to do with being a personal coach? The role of the coach is to help people live better, more fulfilling lives as they pursue their vision and negotiate life’s challenges. The way coaches help people achieve these outcomes is be helping them tap into the wealth of resources that reside within themselves: wisdom, creativity, resourcefulness, strength, and so on. I think these resources reside within that mysterious space I referenced above. So you can add being in a coaching relationship to the list of ways to tap into this space. And being there as a coach when this connection to one’s inner resources happens is just as fulfilling to me as what I felt when, as Anthony’s doc, I was part of a team that helped him survive a life-threatening illness and get home and well again.

by Jeffrey Cohn | Feb 28, 2019 | People with Cancer / Families

People have described the clinical trajectory of a patient with advanced cancer’s life as “falling off a cliff.” This means that the person can seem to be doing relatively well, and then, once the disease exceeds a certain threshold, the person deteriorates progressively, in a relatively short period of time (weeks to months), until death. For most patients with advanced cancer, this metaphor of “falling off a cliff” still applies. So what’s different now? There is a new class of drugs, collectively referred to as “immunotherapy” or “targeted therapy” that, for some people with advanced cancer, can cause the disease to be arrested, even seem to disappear for a few. And this control can occasionally last for a long time- even years. A few oncologists are even using the word “cure.” Continuing with the metaphor, I feel like the individuals for whom these new therapies are working have been given a parachute that opens as they are “falling off the cliff” and allows them to land safely at the bottom, unharmed.

The problem is, we can’t really tell yet which person who is a candidate for these new therapies will benefit and who won’t. And these therapies all have potential toxicities, some severe, some even life-threatening or lethal. So if you’re a person with advanced cancer being offered one of these new therapies, staying with the metaphor, it’s as though you’re given a sack with a parachute in it- but, until you pull your ripcord, you don’t know if it’s a working parachute or one with holes in it. Even worse, these “faulty parachutes” may catch onto ledges or brush along the cliff and cause additional injuries on the way down, making the fall to the bottom even more difficult and painful than if you never had a parachute in the first place.

Before we had these drugs- before we could offer a possibly working parachute- people “knew” what was coming and could prepare. There was some uncertainty regarding

when, and how- but not what was going to happen. This is where our current model of hospice care was developed, and it works pretty well. Knowing you are falling off a cliff without a parachute, caregivers focus on whatever interventions can be provided to have you feel as safe and comfortable as possible. None of this changes what’s going to happen once you reach the bottom, but it makes the fall as easy as it can be. And for your loved ones who will be the survivors, they have as easy a time dealing with their loss as is possible.

Now, with most current regulations, if you receive the parachute and pull the ripcord, hospice care is not an option – at least not until it’s clear that this parachute doesn’t function – and that can be perilously close to the bottom of the fall (i.e., days before end of life). During the time where it’s unknown if and how well this treatment is going to work, you and your family may be (understandably) focusing on hoping for the working parachute, even as you get closer and closer to the bottom. Uncertainty may dominate the experience for much of the time you have. And most of us don’t deal with uncertainty very well.

So what can be done? Palliative care can be a critical support during the fall. This can do much of what hospice care can do, but while still waiting to see if you have a parachute that is going to work, at least for a while. Palliative care can provide medications to treat symptoms causing suffering, spiritual support, care coordination, and care planning for whatever the future might bring. Unfortunately, many communities have little to no access (yet) to community-based palliative care (care outside of the hospital), though that is changing.

I think the most important thing to be done is to talk. In a recent Wall Street Journal article the author described six categories of the kind of things one can talk about with someone who’s on the way down from the top of the cliff. These are: conversations about love, “identity messages” (conversations that frame who you are), religious/spiritual talks, everyday talk, difficult relationship talk (attempting to repair hurt of some kind), and “instrumental death talk” (about funerals, end-of-life care, burial, etc.). To these I would add a few more. I think talking about uncertainty can be supportive. “I imagine it must be hard living with so much uncertainty- about whether this treatment is going to work, about what new symptoms are going to appear, about whether you’ll feel better tomorrow…” or something like that can show empathy and caring about a topic we don’t talk openly about very much. I also think sharing and discussing fears and hopes (the focus of the first two questions from the game Hello) can provide comfort and meaning for the person with the disease, as well as opportunities to help (if asked).

One final use of the metaphor. Maybe conversations are a different kind of parachute, one that opens regardless of how well the first one is functioning. This parachute slows down the fall so that you have time to appreciate various things along the way- the blue sky, the warm air, the cool breeze, everything that makes life worth living. This parachute doesn’t slow you down enough to prevent you from hitting the bottom, but it allows you and everyone you’ve been in conversation with to have found some pleasure and meaning together. Instead of the hard canyon floor being at the bottom of the fall, there is a big, soft pillow. The fall into it is still fatal, but it’s an end that is embracing and comforting, and leaves the survivors capable of getting up from the fall and moving on with their lives with the memories of their loved ones’ words and deeds to guide and comfort them going forward.

Jeffrey Cohn MD, MHCM is a former medical oncologist/hematologist from Ambler, PA. He is currently the Medical Director for Common Practice and a personal/leadership coach for physicians.